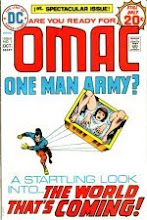

Written by Jack Kirby; Art by Kirby, Mike Royer and D. Bruce Berry; Cover by Kirby and Royer

Witness the early tales of Jack Kirby's legendary creation O.M.A.C. in this hardcover collecting stories from O.M.A.C. #1-8 (1974-1975) plus artwork from WHO'S WHO! In one of his last major works for DC, Kirby envisions a 1984-inspired dystopia starring corporate nobody Buddy Blank, who is changed by a satellite called Brother Eye into the super-powered O.M.A.C. (One Man Army Corps). Enlisted by the Global Peace Agency, who police the world using pacifistic means, O.M.A.C. battles the forces of conformity in this short-lived but legendary series!

Editors;

Legendary,if you conceived crap as legendary.With a look for nestalgic collectors of jack Kirby,but don't roll you eyes of start racking your weener,saying this is great-Kirby is God-because he isn't nor was anything at DC,unless believe all bs by fans and brown nosing creators, and buy hype

Doc Thompson

Thu, June 5th, 2008 at 8:30PM (PDT)

Text Size

Decrease Increase Between the premature halt of his "Fourth World" saga at DC and his return to Marvel in the mid-1970s, Jack Kirby birthed a vision of the future that featured a hero with a blue Mohawk, a giant eyeball in space, Fancy Freddy Sparga, and the mysterious Dr. Skuba. I'm talking, of course, about "O.M.A.C.: One Man Army Corps," which DC has recently released as a hardcover collected edition, using the same cover design as the "Fourth World Omnibus" series. According to the Mark Evanier introduction -- and he would know -- "O.M.A.C." came about because Kirby needed something new to draw to fulfill his monthly DC quota of 15 pages a week. That's right, fifteen pages. Per week. And Kirby was in charge of writing, penciling, and editing each one of those pages. With "The Demon," and "Mister Miracle" at an end, and the success of his post-apocalyptic "Kamandi" series, Kirby was nudged toward another futuristic concept. He'd had an idea for a "Captain America in the future" comic at Marvel a few years earlier, but he decided against it. So take one part future-Cap, one part Kamandi, 98 parts Kirby genius, and mix them in a super-space blender, and -- presto! -- "O.M.A.C.: One Man Army Corps."

The series only lasted eight issues -- all of which completely written and drawn by Kirby. Issue #8 even ends with a question, "Is this -- the end?" The answer: I guess so. Because no more Kirby "O.M.A.C." issues were ever released. So the question for today's reader becomes: "Is this hardcover edition worth my twenty-five bucks? Or is this just a desperate money-grab by DC since the Fourth World Omnibuses sold a few copies?" My answers: yes, and yes. A desperate money-grab though it may be -- as everyone seems willing to put out Kirby hardcovers all of a sudden, at Marvel, DC, and even Image -- it's still Kirby in his prime. I've argued for years, to anyone who would listen -- which was a small population, to be sure -- that Kirby's 1970s work was far more transcendent and dynamic than anything he produced in collaboration with Stan Lee a decade earlier. Yes, the "Fantastic Four" run is phenomenal, but Kirby got even better as an artist once he began doing his own stuff in the Bronze Age. His page layouts exploded, his characters became even more geometric, and his ideas become weirder and weirder (in a great way).

"O.M.A.C." isn't one of his strangest concepts, but it's a solid example of his work during that era. It fails to reach the cosmic heights of either the "Fourth World" stuff or his later "Eternals" series, and it doesn't have the manic strangeness of "Kamandi," but it's still a series about a Mohawk-sporting super-cop from the future, who hangs out with faceless dudes, and was madly in love with a "build-a-friend" doll.

In the introduction, Evanier also talks about how much more "real" and relevant this series has become since it first premiered. He indicates that we are "edging closer to the era of Buddy Blank," and that has made him appreciate this long-underappreciated series all the more. With all due respect to Evanier, I don't think relevance is what makes "O.M.A.C." work. What makes it work and what makes it worth your time is the madness of Dr. Skuba, who attempts to corner the market on water by sucking up all of the oceans into handy-dandy "bars" he can carry around in his flying red ship. Or Mr. Big, who rents out an entire city for his own private amusement, until O.M.A.C. busts in to stop the fun. Or the double-page spreads of fresh young bodies getting sold to the highest bidder, for brain transplants!

Admittedly, D. Bruce Berry is not Kirby's best inker, and he embellishes the bulk of the issues in this story (although Mike Royer -- arguably the ideal Kirby inker -- does handle the first and the last). And some of these pages look and feel like they were just cranked out by Kirby working on fumes. But what amazing fumes they were! "Jack Kirby's O.M.A.C.: One Man Army Corps" may not be Kirby's best work, but it's still full of more energy and ideas than fifty other comics by anyone else. Is it worth the twenty-five bucks. You bet it is.

OMAC-ONE MAN ARMY CORPS ? OR ONE MAN ARMY CORPSE ?

In a strange parallel, Blank becomes O.M.A.C. to rescue his attractive co-worker, only to learn that she herself is a faux human created as a bomb; Blank indeed becomes much the same. There's an odd scene a few issues in where the GPA introduces the O.M.A.C. to its new volunteer parents, whose purpose is never quite explained (Blank, we presume, had parents of his own). There's a sense that the GPA recognizes they've stolen Blank's identity from him, even if they're not moved enough to release him, and so tries to offer a substitute for love without understanding the inherit impossibility of doing so.

Indeed there's much that was once genuine in "the world to come"--as Kirby's calls the future in which O.M.A.C. takes place--that's now been commodified. Blank's original employer Pseudo-People sold faux people for companionship, and later for assassination. The villain Mr. Big, in another story, rents an entire city for a private party, forcing the city residents to remain off the streets all night--and then he, too, turns the city into a trap for O.M.A.C.

Kibry's future is a world that money can buy anything, and anything that can be bought can be repurposed to kill--often in the pursuit of more money. Concepts like emotions have become commodities, and even as the story's hero fights his equivalent villains, it seems that neither the Peace Agency nor the villains are immune to the corruptive nature of this society, with O.M.A.C. caught in the middle.

Jack Kirby never finished his O.M.A.C. saga, ending the series rather abruptly, and his former assistant Mark Evanier in his introduction puzzles over, but never offers answers to, the story's meaning. Surely there's something just a little sinister intended in the Global Peace Agency, and an allegory hidden in the GPA having transformed Buddy Blank into the ultimate weapon and then inexplicably promoting him to an extent that no GPA member can give him orders, effectively ceding control of said weapon.

Also telling is the final story in which an increasingly sympathetic villain fights the GPA's Brother Eye satellite in a battle of man versus machine that leaves the reader unsure whom to root for.

Kirby's O.M.A.C. is deceptive--seemingly the story of a covert intelligence group that fights for peace, it's instead a treatise on the futility of that fight. Kirby presents O.M.A.C. as simultaneously a warrior and a victim, and in doing so reveals the shortfalls of the cause to which O.M.A.C. is drafted.

Constant readers know I'm not much for pre-Crisis storytelling, and indeed there's not much of a constant, driving plot in this O.M.A.C. collection, but the sheer volume of what Jack Kirby's trying to say here makes it worth the read (if not for the sheer number of Countdown to Final Crisis in-jokes I understand better now). Certainly this volume deserves a place on your bookshelf next to your other Jack Kirby omnibuses.

[Contains full covers, introduction by Mark Evanier, sketch pages. See more reviews of O.M.A.C. from Timothy Callahan, Val Jensen, and Paul Smith]

We rejoin the fight now with Countdown to Final Crisis Volume 3, coming up next

.bp.blogspot.com/__ZwgBbykKVA/SoBpMWre_CI/AAAAAAAAAE8/4YnU_buc6hs/s320/jomwc1.jpg" border="0" alt=""id="BLOGGER_PHOTO_ID_5368406416792943650" />

Wikipedia is sustained by people like you. Please donate today.The Wikimedia Board of Trustees election has started. Please vote. [Hide]

[Help us with translations!]

One-Man Army Corps

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Jump to: navigation, search

It has been suggested that this article or section be merged into OMAC (comics). (Discuss)

For the OMAC cyborgs, see OMAC (comics).

One-Man Army Corps (OMAC)

Cover to OMAC #6, with the original OMAC. Art by Jack Kirby.

Publication information

Publisher DC Comics

Created by Jack Kirby

In-story information

Alter ego Buddy Blank

Team affiliations Global Peace Agency

Abilities Superhuman strength, speed, durability and explosive energy generation provided by Brother Eye

OMAC (One-Man Army Corps) is a superhero comic book created in 1974 by Jack Kirby and published by DC Comics. The character was created towards the end of Kirby's contract with the publisher, following the cancellation of Kirby's New Gods[1], and was reportedly developed strictly due to Kirby needing to fill his monthly quota for 15 pages a week [2].

Contents [hide]

1 Publication history

2 Powers and abilities

3 Alternate versions

3.1 OMACs

3.2 Other

4 Other Media

4.1 Television

4.2 Video Games

4.3 Toys

5 Collected editions

6 References

7 External links

[edit] Publication history

Set in the near future ("the world that's coming"), OMAC is a corporate nobody named Buddy Blank who is changed via a "computer-hormonal operation done by remote control" by an A.I. satellite called Brother Eye into the super-powered One-Man Army Corps (OMAC)[3].

OMAC works for the Global Peace Agency (GPA), a group of faceless people who police the entire world using pacifistic weapons. The world balance is too dangerous for large armies, so OMAC is used as the main field enforcement agent for the Global Peace Agency[4]. The character intially becomes the Ares like war machine to save a female coworker at the Pseudo-People factory (manfactures of androids intitially intended as companions, but later developed as assassins). The coworker is revealed to be in actuallity a bomb, and Blank is left in the employ of the GPA, sacrificing his identity in their relentless war, with faux parents his only consolation and companions[5].

OMAC series lasted for eight issues(1974-1975), which was cancelled before the last storyline was completed, Kirby writing an abrupt ending to the series. Later, towards the end of Kamandi (after Kirby had left that title), OMAC was tied into the backstory and shown to be Kamandi's grandfather. An OMAC back-up feature by Jim Starlin was started in issue #59, but the title was cancelled after the first appearance. It would later finally see print in Warlord, and a new back-up series would also appear in that title (#37-39, 42-47). OMAC made appearances as a guest alongside Superman in DC Comics Presents #61.

In 1991 OMAC was featured in a four-issue prestige format limited series by comic artist and writer John Byrne that tied up loose ends left from previous stories. John Byrne would later reuse OMAC in his Generations 3 mini-series.

In Countdown to Final Crisis, Buddy Blank is featured as a retired, balding professor with a blond-haired grandson. In #34, Buddy Blank is mentioned but not seen, and is referred to as having direct contact with Brother Eye. He is contacted by Karate Kid and Una in Countdown #31, and appears in #28 and 27. A version of Buddy from Earth-51 appears in #6 and #5 where the Morticoccus virus is released. Buddy spends the rest of the time holed up in a bunker with his grandson who is revealed to be "Kamandi". In the final issue, Countdown to Final Crisis #1, Brother Eye rescues Buddy and his grandson from the ruins of Blüdhaven by turning him into a prototype OMAC with free will, resembling the original Jack Kirby OMAC.

[edit] Powers and abilities

Through interfacing with the Brother Eye satelite, via invisible beam to his receiver belt[6], Buddy Blank is transformed into OMAC and imbued with an array superhuman abilites. The base of abilities involve density control of Blank's body. Increase in density leads to an increase in super-strength and enhanced durability[7], while a decrease in density leads to flight and super-speed. Brother Eye could provide other abilites as well, such as self-repairing functions.

[edit] Alternate versions

[edit] OMACs

The modern OMAC. Cover to The OMAC Project #5. Art by Ladrönn.Main article: OMACs

The character, along with the Brother Eye satellite, was reimagined for the 2005-2006 Infinite Crisis story arc. OMACs are portrayed as cyborgs, humans whose bodies have been taken over via a nano-virus. The characters retain OMAC's familiar mohawk and Brother Eye symbol on their chest. The characters are featured in the OMAC Project limited series which leads up to Infinite Crisis, and subsequent OMAC limited series. The acronym has multiple meanings through the series: Observational Meta-human Activity Construct, [8], One-Man Army Corps[9], "Omni Mind And Community."[10]

[edit] Other

DC Comics', in its Tangent Comics imprint issue The Joker's Wild in 1998, self-parodied OMAC with a beta-version automated policeman called "Omegatech Mechanoid Armored Cop".

DC would later make a nod to OMAC during the DC One Million event in 1998. In Superboy 1,000,000, one of the future Superboys is known as Superboy OMAC, or "One Millionth Actual Clone", and the title of the story was "One Million And Counting", repeating the acronym. He appeared in the Superboy and Young Justice specials, as well as the DC One Million mini-series. His appearance is based on OMAC, and he gains increased power from Brother Eye.

In Kingdom Come, Alex Ross created a female version of OMAC named OWAC, (One-Woman Army Corps).

The One Million 80 Page Giant also introduced a female Luthor with OMAC elements who called herself the One Woman Adversary Chamber.

OMAC made a brief appearance in Elseworlds' JLA: Another Nail when all time periods meld together.

Some basic OMAC units resembling the first OMAC were featured in Final Crisis.

[edit] Other Media

[edit] Television

OMAC from Batman: Brave and the Bold episode When OMAC Attacks!.The original OMAC, Buddy Blank, will appear in the animated series Batman: The Brave and the Bold voiced by Jeff Bennett. In the episode "When OMAC Attacks!", OMAC battles Shrapnel in a long and destructive battle arranged by Equinox.[11] In this, Buddy did not know he was OMAC until Batman tells him his purpose. While OMAC handles Shrapnel, Batman interrogates and fights Equinox. Shrapnel is eventually brought to justice by OMAC, Buddy Blank bought time for Batman to stop a nuclear meltdown by distracting Equinox after he detransformed.

[edit] Video Games

Batman's ending in Mortal Kombat vs. DC Universe involves him creating "OMAC" (Outerworld Monitor and Auto Containment) robot versions of Batman to maintain the balance between Earthrealm and DC Universe. It is designed to monitor and trap invaders from different universes.

[edit] Toys

It was announced at New York Comic Con 2009 that OMAC will be released as a figure in the Justice League Unlimited toyline down the road.

[edit] Collected editions

Jack Kirby's O.M.A.C.: One Man Army Corps (hardcover, DC Comics, May 2008, ISBN 1401217907)[12]

[edit] References

^ http://www.amazon.com/Jack-Kirbys-O-M-C-Kirby/dp/1401217907

^ http://www.comicbookresources.com/?page=user_review&id=162

^ www.eeweems.com/artandartifice/paul_pope.html

^ http://collectededitions.blogspot.com/2009/03/review-jack-kirbys-omac-one-man-army.html

^ http://collectededitions.blogspot.com/2009/03/review-jack-kirbys-omac-one-man-army.html

^ http://warren-peace.blogspot.com/2008/06/vacation-guestblogstravaganza-jones.html

^ http://www.schoollibraryjournal.com/article/CA6611756.html?q=omac

^ The OMAC Project #1

^ The OMAC Project #5

^ The OMAC Project #6

^ worldsfinestonline.com/WF/bravebold/guides/s01.php

^ Jack Kirby's O.M.A.C.: One Man Army Corps profile at DC

[edit] External links

Review of Jack Kirby's O.M.A.C.: One Man Army Corps, Comic Book Resources

OMAC (Buddy Blank) at the Comic Book DB

OMAC (Michael Costner) at the Comic Book DB

OMACs at the Comic Book DB

OMAC (1974) at the Comic Book DB

OMAC: One Man Army Corps at the Comic Book DB

The OMAC Project at the Comic Book DB

OMAC (2006) at the Comic Book DB

Retrieved from "http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/One-Man_Army_Corps"

Categories: 1974 comic debuts | 1991 comic debuts | 2006 comic debuts | Comic book alternate futures | Comics by Jack Kirby | DC Comics science fiction characters | DC Comics superheroes | Post-apocalyptic comics | Characters created by Jack Kirby

Hidden categories: All articles to be merged | Articles to be merged from August 2009 | Character pop | Converting comics character infoboxesViewsArticle Discussion Edit this page History Personal toolsTry Beta Log in / create account Navigation

Main page

Contents

Featured content

Current events

Random article

Search

Interaction

About Wikipedia

Community portal

This page was last modified on 10 August 2009 at 17:43. Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License; additional terms may apply. See Terms of Use for details.

Wikipedia® is a registered trademark of the Wikimedia Foundation, Inc., a non-profit organization. Privacy policy About Wikipedia Disclaimers

Published 1959

Posted by bob at 12:22 PM 2 comments

Saturday, June 25, 2005

OMAC #1 - Brother Eye and Buddy Blank

Brace yourselves for "The World That's Coming".

OMAC ##1 is some strange stuff even by 1970s Kirby standards. What can you make of a book that opens with a full page splash of a disassembled robot woman "Build-A-Friend" in a box saying "Hello -- Put me together and I will be your friend"? Just plain weird.

Also, kind of an unusual story structure for Kirby, as he opens with the climax of the story, then has a flashback to the origin building up to the first scene and then the conclusion. It works pretty well, as it moves the action right up to the front and sets up the rest of the issue nicely.

Anyway, after seeing OMAC bring down the Build-A-Friend shop, we flashback to his origin, as the faceless Global Peace Agency tell Dr. Myron Forest that they have selected Buddy Blank to be the subject of the OMAC Project, leaving Forest to activate the sleeping satellite Brother Eye. After a view of Buddy's life at the offices of Pseudo-People, Inc. and some bizarre scenes of their "psychology section", we see that he was befriended by the previously revealed to be a Build-A-Friend Lila, as part of an experiment in making lifelike beings. As Buddy stumbles onto the secret section and finds out the secret of Lila and the nefarious assassination plans she's to be part of, Brother Eye transforms him to OMAC.

A wonderful issue, brilliant in its almost pure oddball insanity, if Kirby comics were drugs this issue would be the equivalent of mainlining uncut Kirby. Even the artwork seems like a heightened pure version of Kirby. Not for the faint of heart or uninitiated.

If you say so.Me I saw it as crap,from a tired,old comic artist,with big rep in the industry and a multitude of fanatic,braindead fans.

Doc Thompson

Mike Royer inks the 20-page story and the cover (which is a flipped version of the original art Kirby did for the cover). Kirby also writes a text page about how rapidly the world has changed and will continue to change, including the mention that part of the inspiration for this issue comes from seeing the "autitronic robots" during a trip to Disneyland with his granddaughter.

Published 1974

Posted by bob at 11:04 PM 1 comments

First you can't a name like OMAC-which stands for One Man Army Corp.

One is the integer before two, and after zero. One is the first non-zero number in the natural numbers as well as the first odd number in the natural numbers.

Any number multiplied by one is the number as it is an identity for multiplication. As a result, one is its own factorial, its own square, its own cube and so on. One is also the empty product as any number multiplied by one is itself, which is the same as multiplying by no numbers at all.

Man

"Men" redirects here. For other uses, see Men (disambiguation).

Michelangelo's David is the classical image of youthful male beauty in Western art.A man is a male human. The term man (irregular plural: men) is used for an adult human male, while the term boy is the usual term for a human male child or adolescent human male. However, man is sometimes used to refer to humanity as a whole. Sometimes it is also used to identify a male human, regardless of age, as in phrases such as "Men's rights".

The term "manhood" is used to refer to the various qualities and characteristics attributed to men such as strength and male sexuality

An army (from Latin Armata "act of arming" via Old French armée), in the broadest sense, is the land-based armed forces of a nation. It may also include other branches of the military such as an air force. Within a national military force, the word Army may also mean a field army, which is an operational formation, usually made up of one or more corps.

A Corps (pronounced /ˈkɔər/ "core"; plural /ˈkɔərz/ spelled the same as singular; from French, from the Latin corpus "body") is either a large formation, or an administrative grouping of troops within an armed force with a common function such as Artillery or Signals representing an arm of service. Corps may also refer to a branch of service such as the United States Marine Corps, the Corps of Royal Marines, the Honourable Corps of Gentlemen at Arms, or the Corps of Commissionaires.

So,if you understand what those words mean,OMAC stands for a single or first,human male,act of arming or armed body or large formation or grouping or branch of the service.Does this actually say some big jerk,in blue and yellow or orange tight,with sideburns and mowhawk or does say something else ?It could a guy or a single group of solders in the army.

Omac and Buddy Blank,were just action comic meat puppets,with no real personality.The Global Peace Agency were a bunch of insentitive creeps,who took a smuck,with his permission and turned him into a hero.If you guys can't see how wrong this way,then I don't know what else to say.